.

Debordering Tijuana:

Ad Hoc Urbanism Towards Intracity Reconciliation

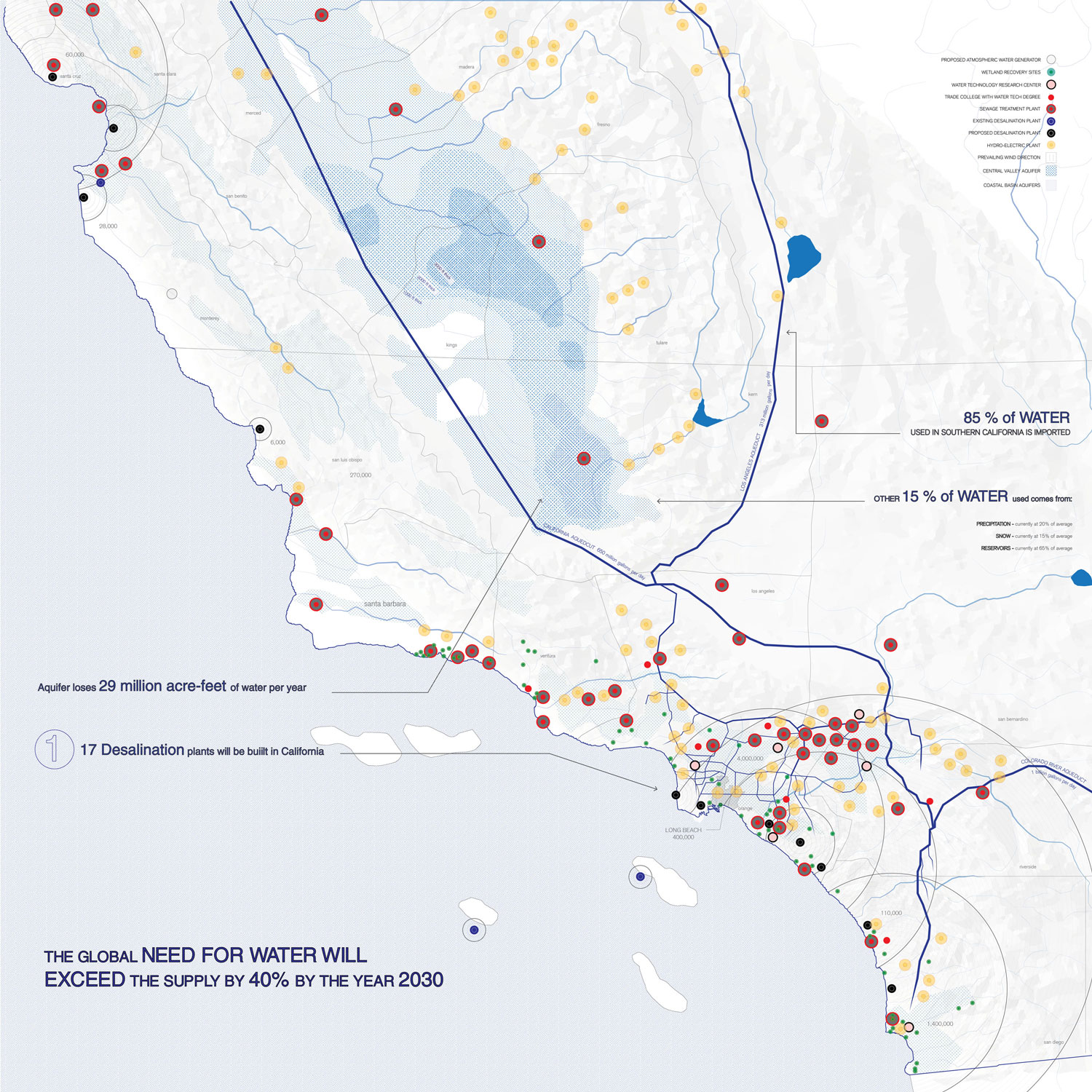

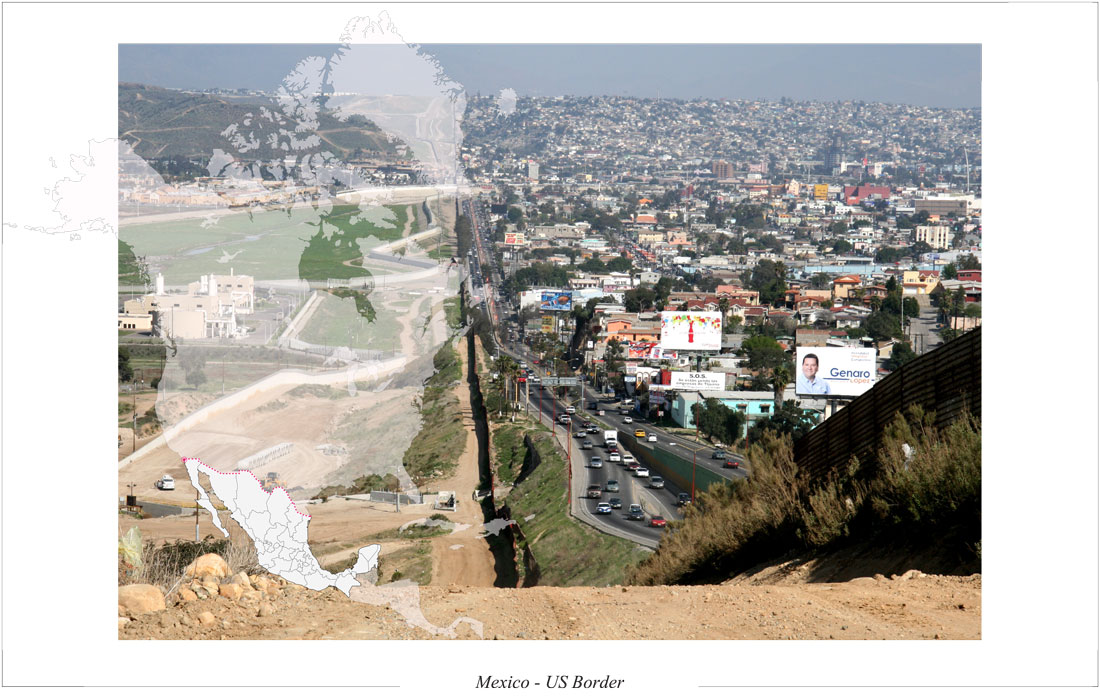

A border located in space is the result of the social practice of difference[1]. In other words, a border is a physical manifestation of the social construct of an other. Tijuana, Mexico sits at the furthermost northwestern border between Mexico and the United States. While the function of a border is to delineate the extent of a jurisdiction, Tijuana’s intracity borders are divisive not only spatially, but also socially. Tijuana’s post-NAFTA development has turned it into a post-colonial dual city where urban sprawl is characterized by polarity and stark wealth disparity.

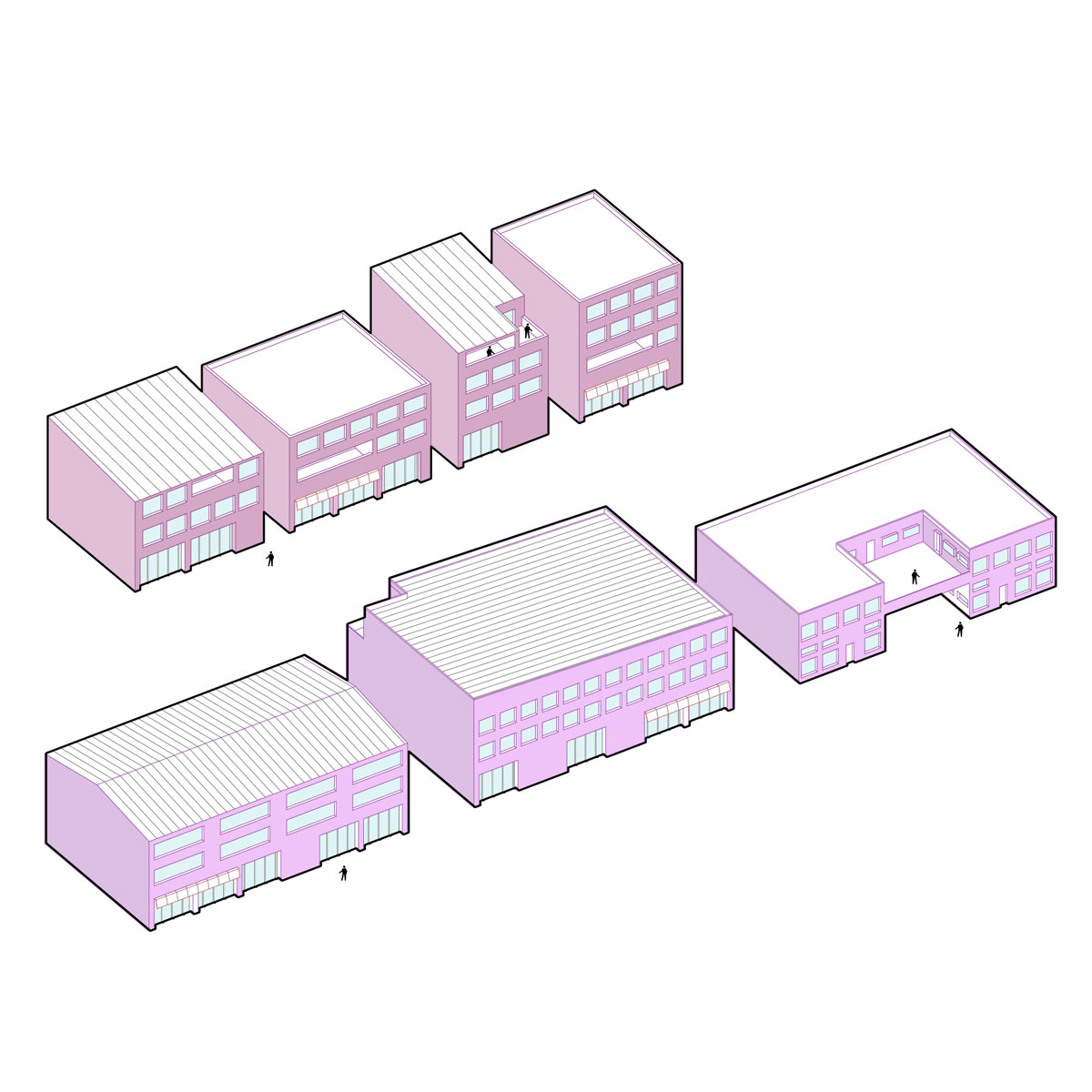

Premised on the conception of house-as-machinethat reconciles divisions and leverages the intersection of different components, this project found a house typology that, through a common set of aesthetic decisions, reveals aspirations that are common across income brackets and challenge notions of single family occupancy. The Tijuana House is used as a point of departure towards reconciliation in the city. By formalizing the ad hoc nature of the Tijuana House, the lessons learned can be translated and redeployed across scales.

This project challenges Tijuana’s instituted norm to default to American systems of space and use organization. To be able to combat sprawl and division, the city can instead appropriate its own principles of dwelling to reconfigure the mixed-use type, stimulate a tighter proximity of intracity borders, and consolidate its thresholds.

[1] Henk Van Houtum and Ton Van Naerssen, Bordering, Ordering and Othering, 2001.

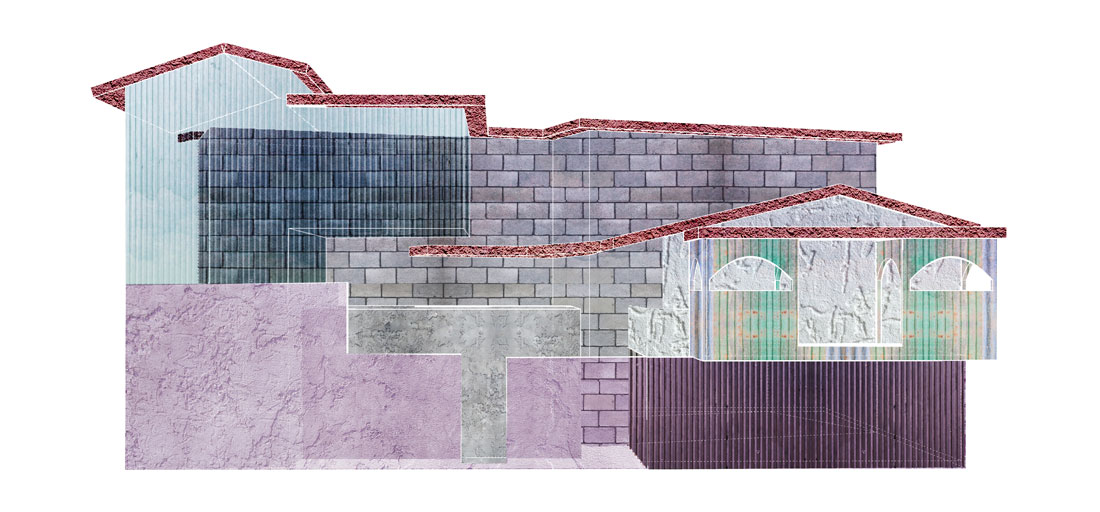

As I browsed the city in search for commonality

between social and economically segregated areas, I found several houses that

demonstrated very similar attributes regardless of location and affluency.

Somebody decided to aggregate different components, with different building materials in to this unit. It is an aesthetic decision to paint it all the same color, as to unify.

Window types, gates, and wall finishes, all have a certain intentionality.

Different from certain dwellings that are clearly collaging whatever is at their disposal, which embodies a whole different set of issues, the Tijuana house emerges from a place of aspiration and not so much from a place of need.

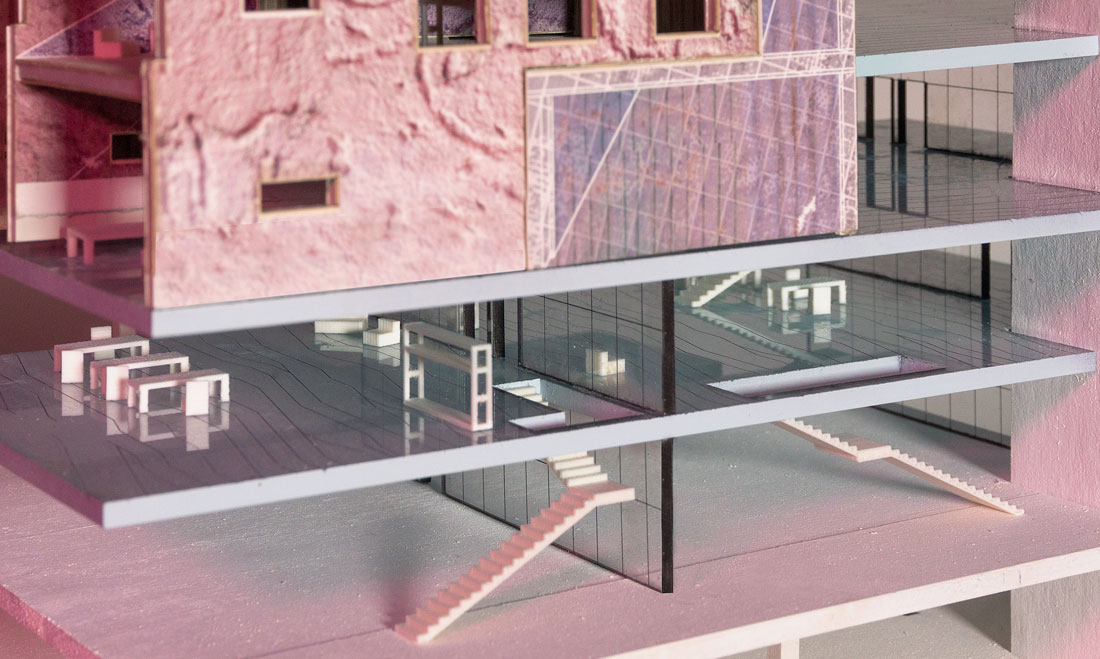

The Tijuana house thrives through its heterogeneity. It operates as an aggregation diagram that cohesively brings together different components.

Somebody decided to aggregate different components, with different building materials in to this unit. It is an aesthetic decision to paint it all the same color, as to unify.

Window types, gates, and wall finishes, all have a certain intentionality.

Different from certain dwellings that are clearly collaging whatever is at their disposal, which embodies a whole different set of issues, the Tijuana house emerges from a place of aspiration and not so much from a place of need.

The Tijuana house thrives through its heterogeneity. It operates as an aggregation diagram that cohesively brings together different components.

I argue that, in these houses lies the potential to begin to bridge the differences that are found at the urban scale, and that they can be utilized as a point of departure towards the reconciliation of borders in the city.

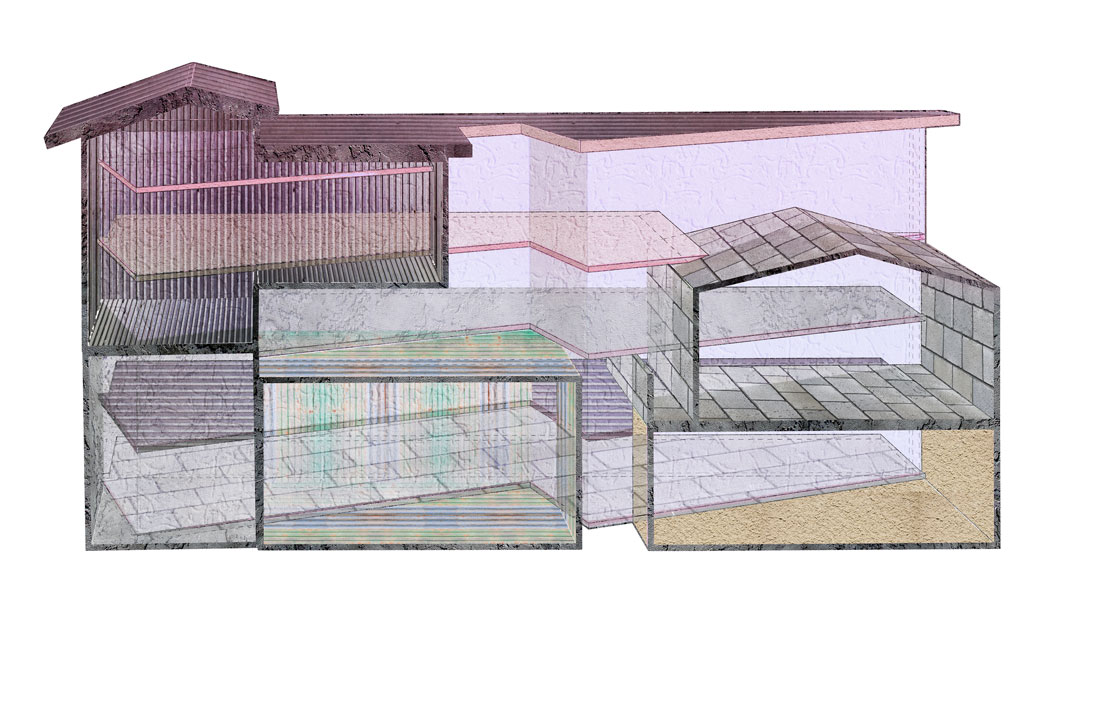

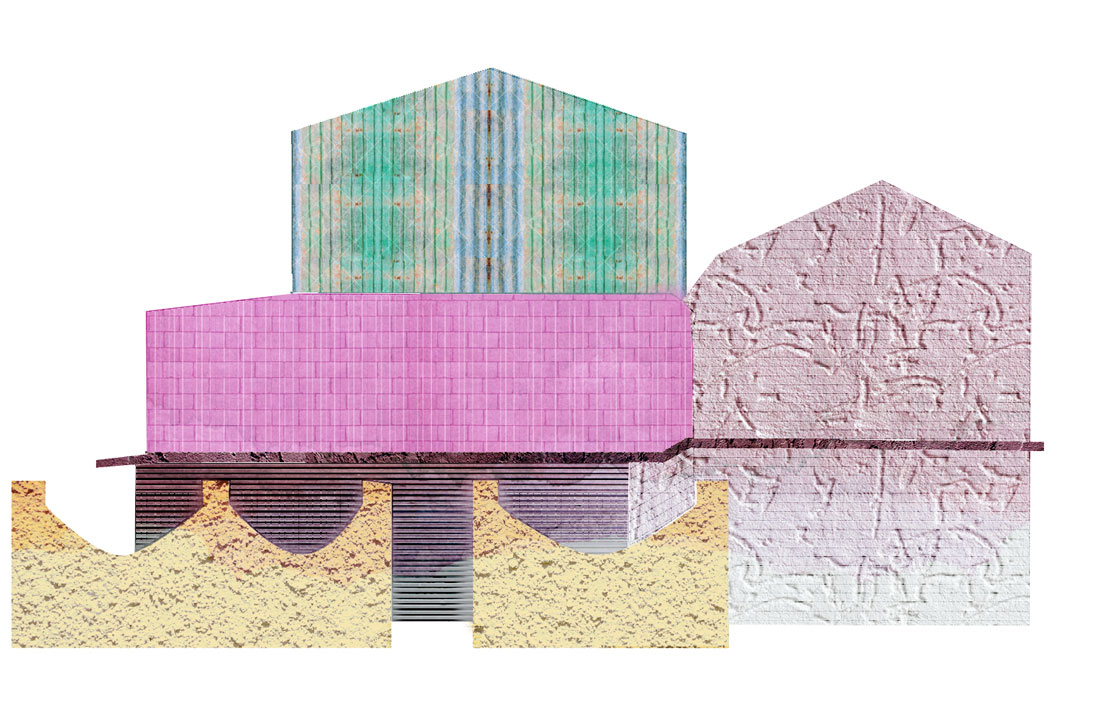

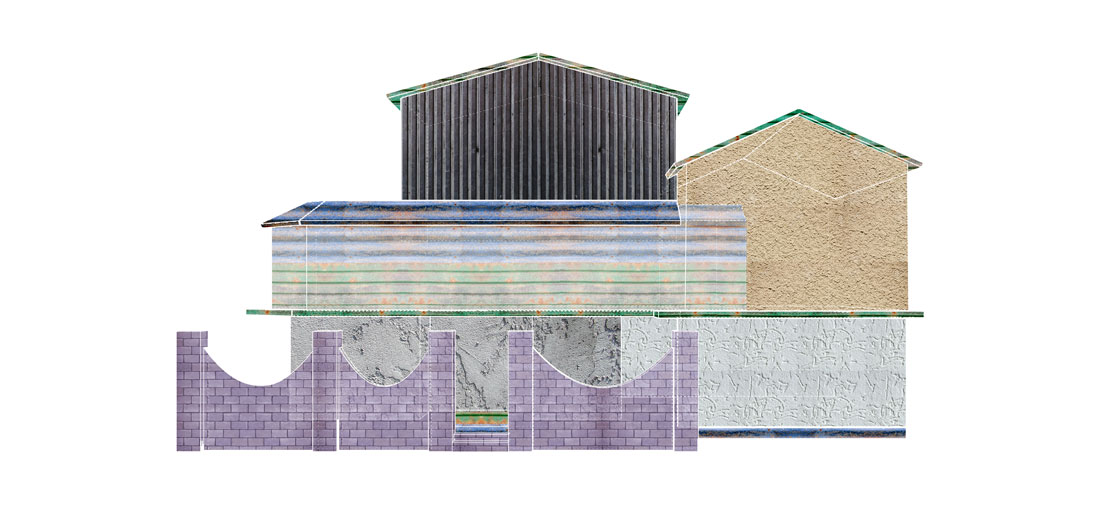

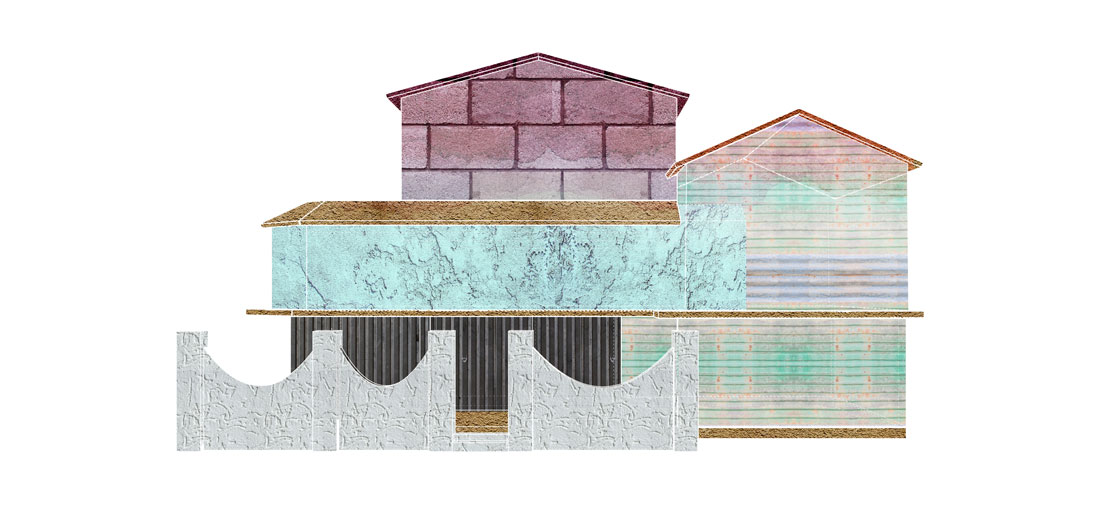

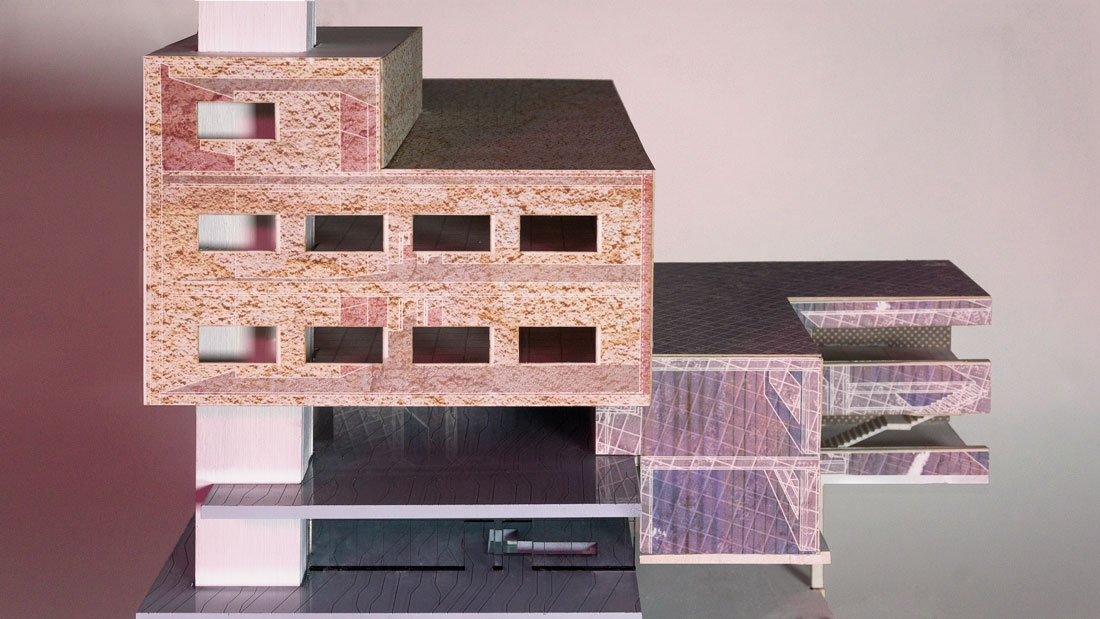

These house collages served as early studies that aimed to find the more subtle differences that stand in contrast to the more aggressive juxtaposition of different masses. All as to understand the different ways in which the houses perform, in their unique inhabitation, beyond the elevation.

They began as an exploration of Tijuana’s visuality, but culminate in the development of a method of representation that blurs conditions, exploiting the way in which these houses deal with difference and highlights how people build over time, accumulate, layer.

Taking that freedom of intermixing materiality found in the house –the collage served as a medium to begin to draw metaphors that allowed to think through the city.

Tijuana, with its divisions at an urban scale seems to be failing where the Tijuana House in all its difference seems to be thriving.

Tijuana’s habit of zoning large areas of sameness tends to leave entire

neighborhoods isolated.

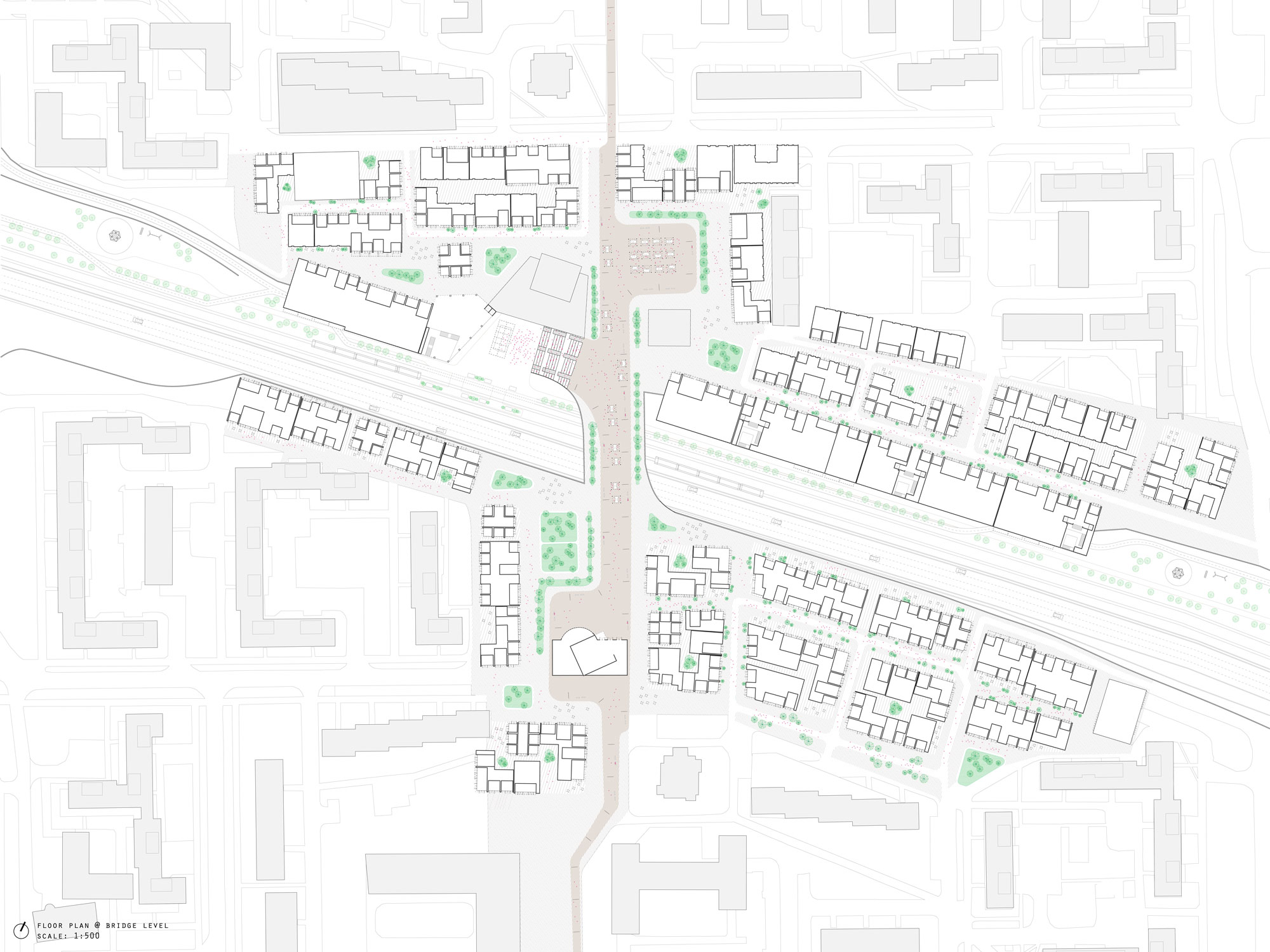

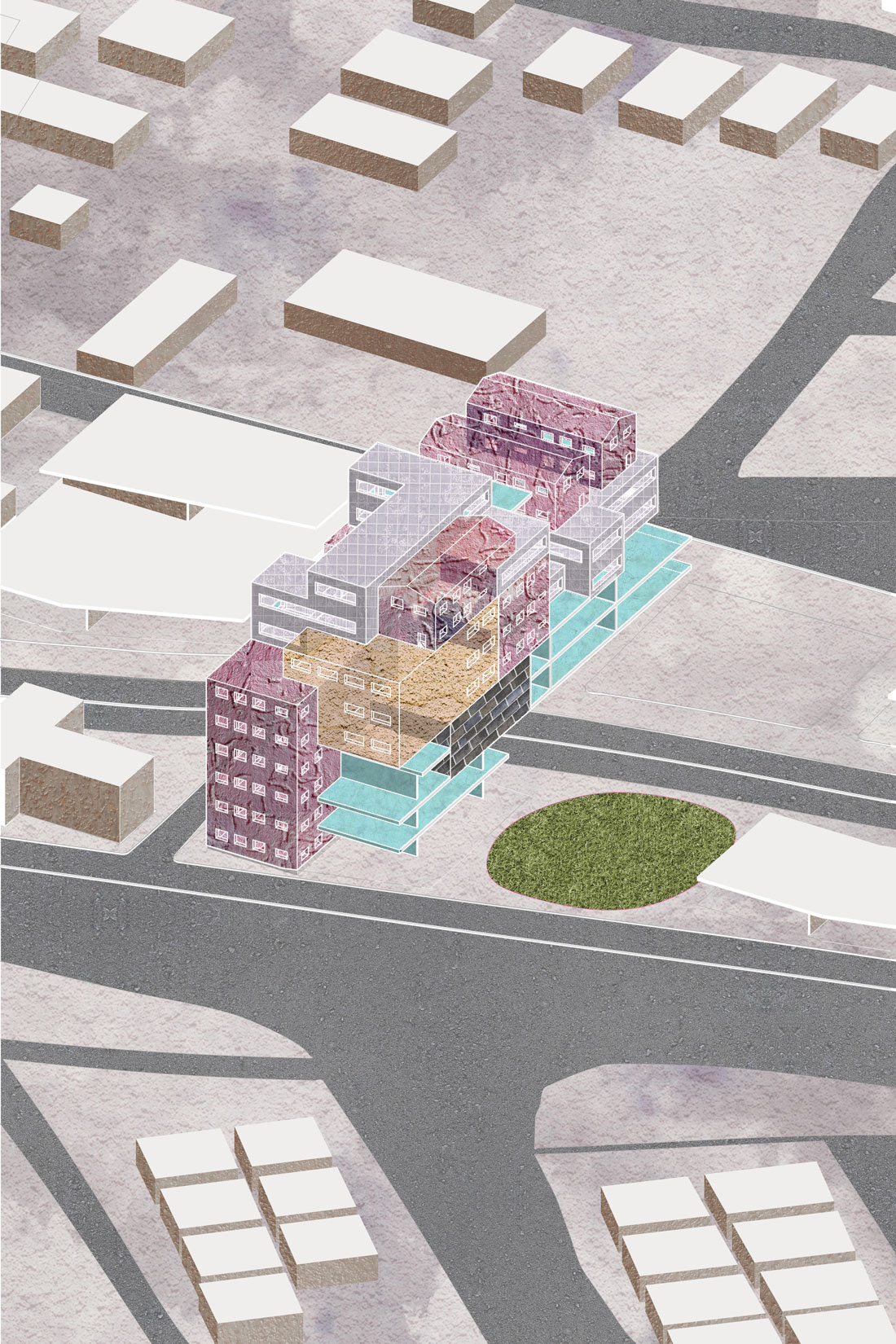

The site of my intervention is located at the center

of various colliding divisions. Topographically, it sits in a valley, at the

foot of the Cerro Colorado Hill. And its south boundaries are defined by a main

highway intersection. Although physically close to a major circulation artery,

the area is extremely isolated, even in car, it has a complicated access.

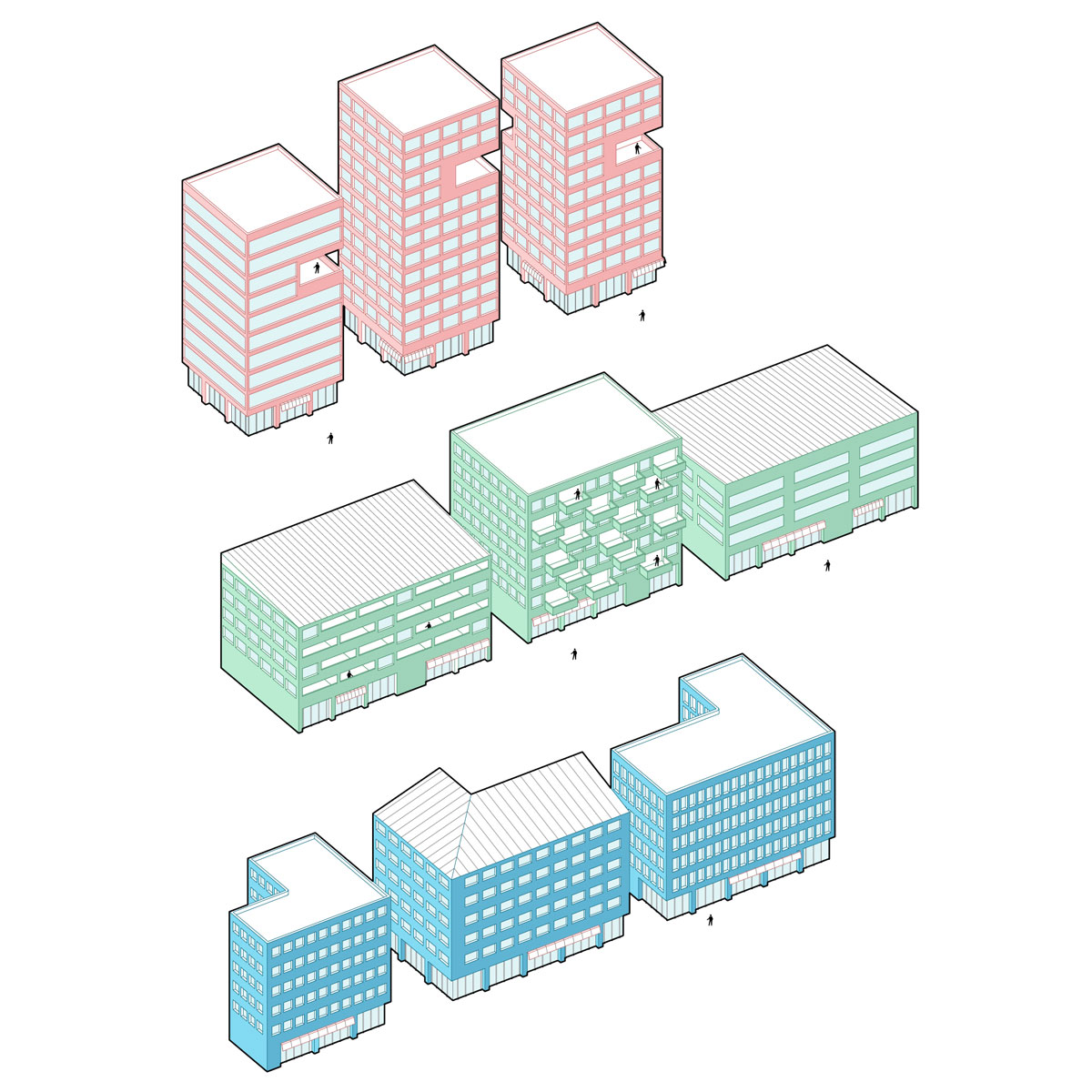

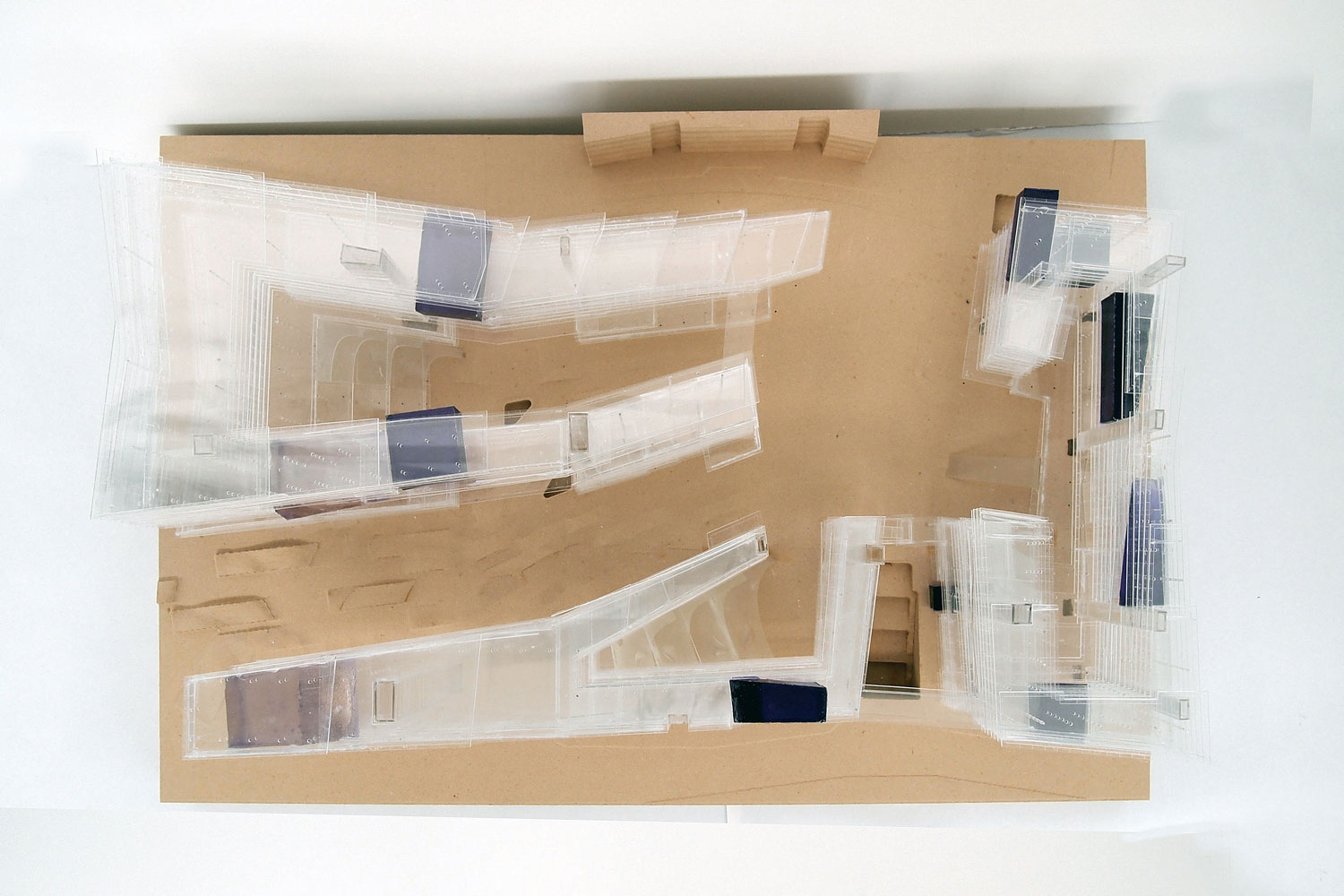

The goal at this scale is to design a prototype neighborhood that demonstrates ways in which the city can begin to leverage its divisions, not only to bridge inherently segregated areas, but to reconfigure the way uses are mixed and re-negotiate the city’s limit on density.

The goal at this scale is to design a prototype neighborhood that demonstrates ways in which the city can begin to leverage its divisions, not only to bridge inherently segregated areas, but to reconfigure the way uses are mixed and re-negotiate the city’s limit on density.

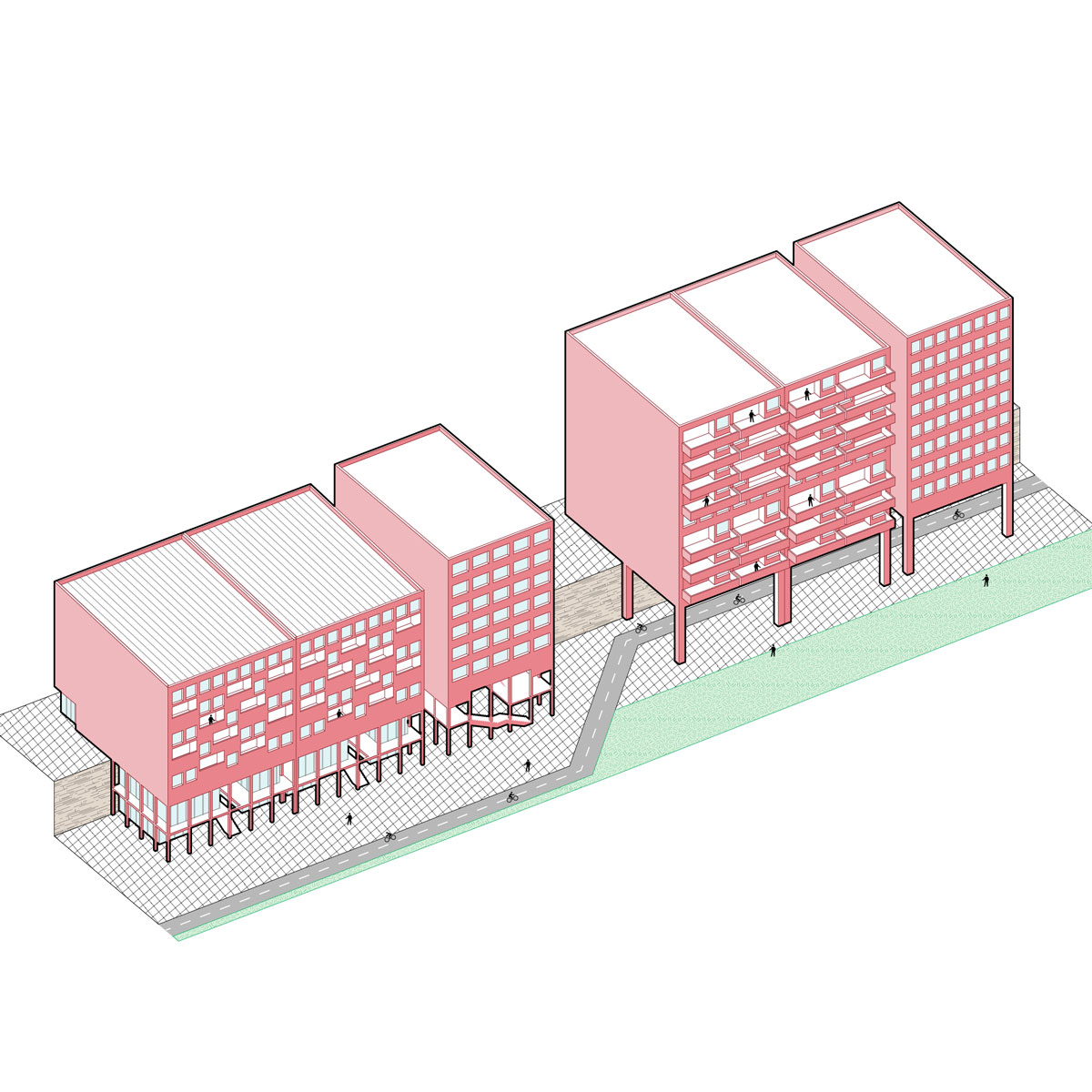

At a much larger scale, I bring back the Ad hoc strategies to recreate

the mixing affects of the Tijuana House. By pixelating further, these projects hope

that the hybridization of uses and programs can influence its surroundings.

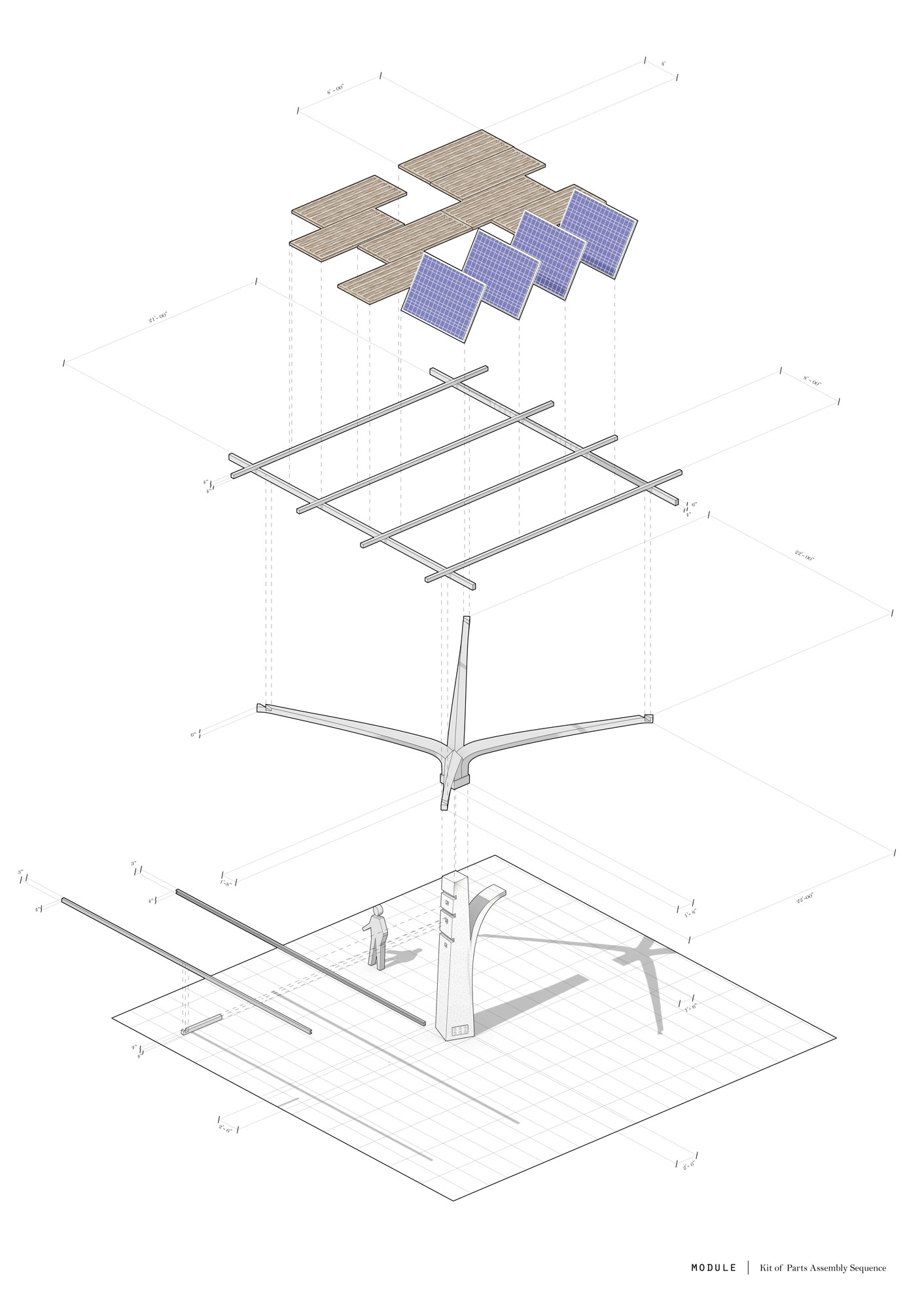

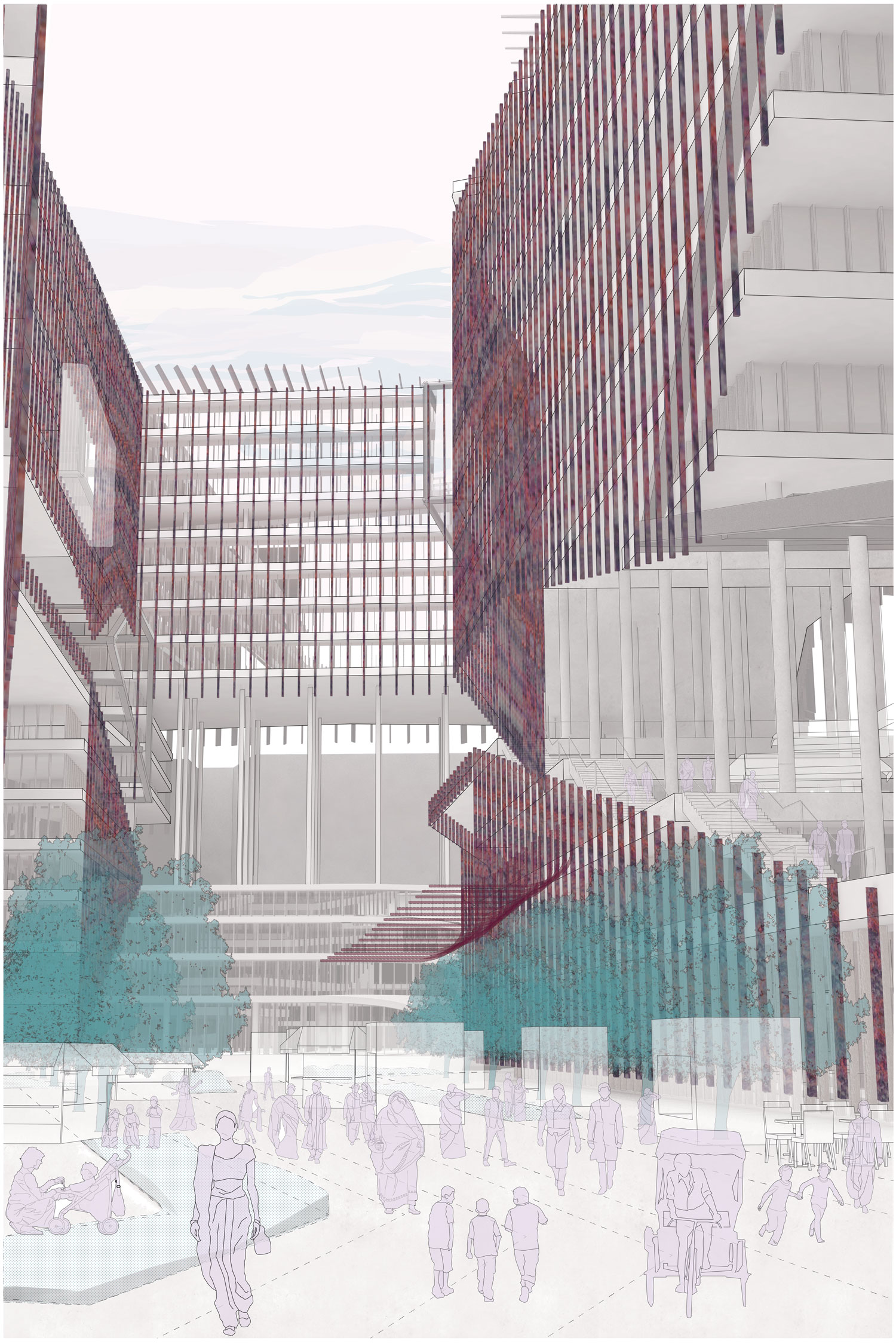

Bhartiya City Tech Campus

Team Members: Matthew Chang, Morgan Feng, and Sabrina Ramirez-Diaz

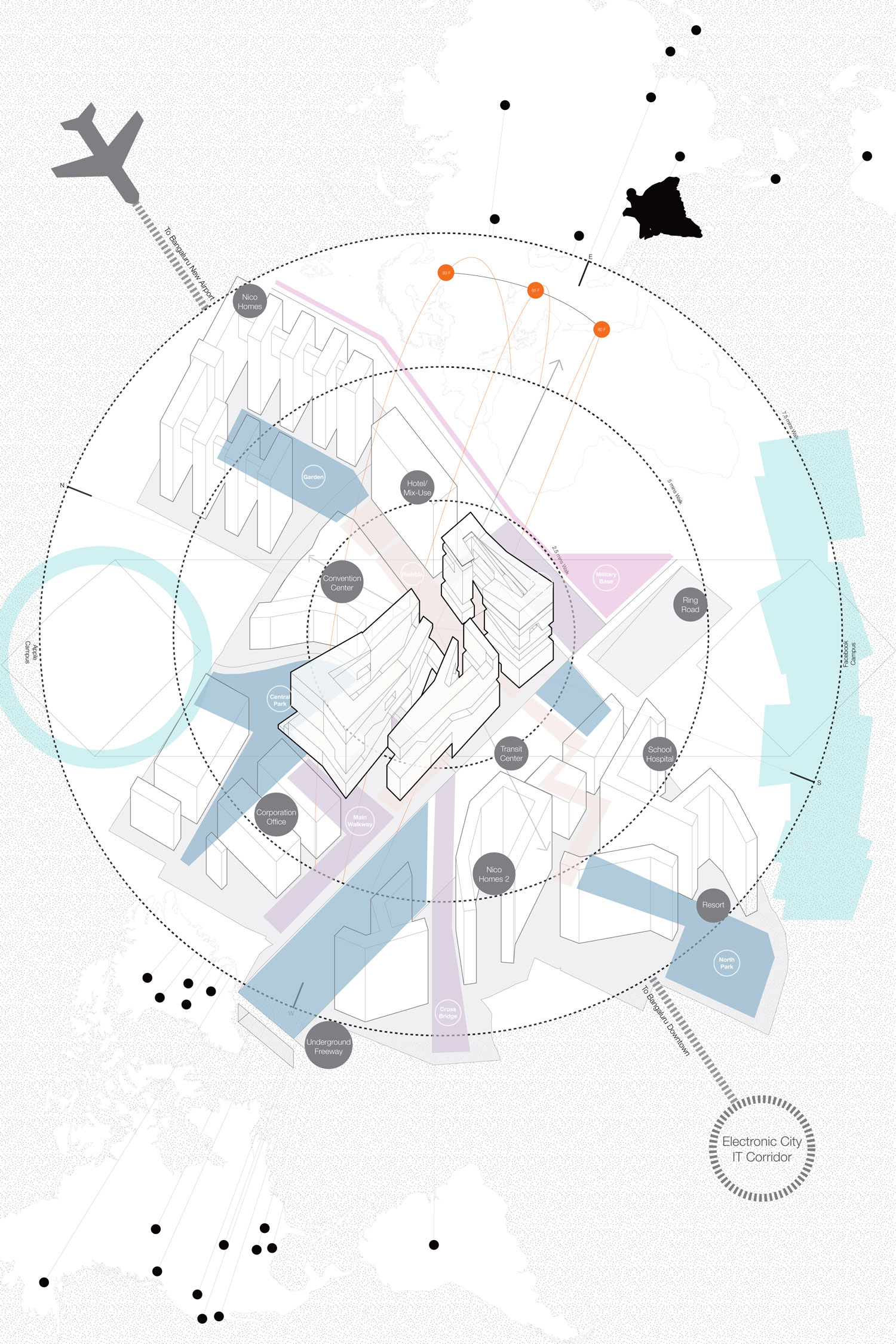

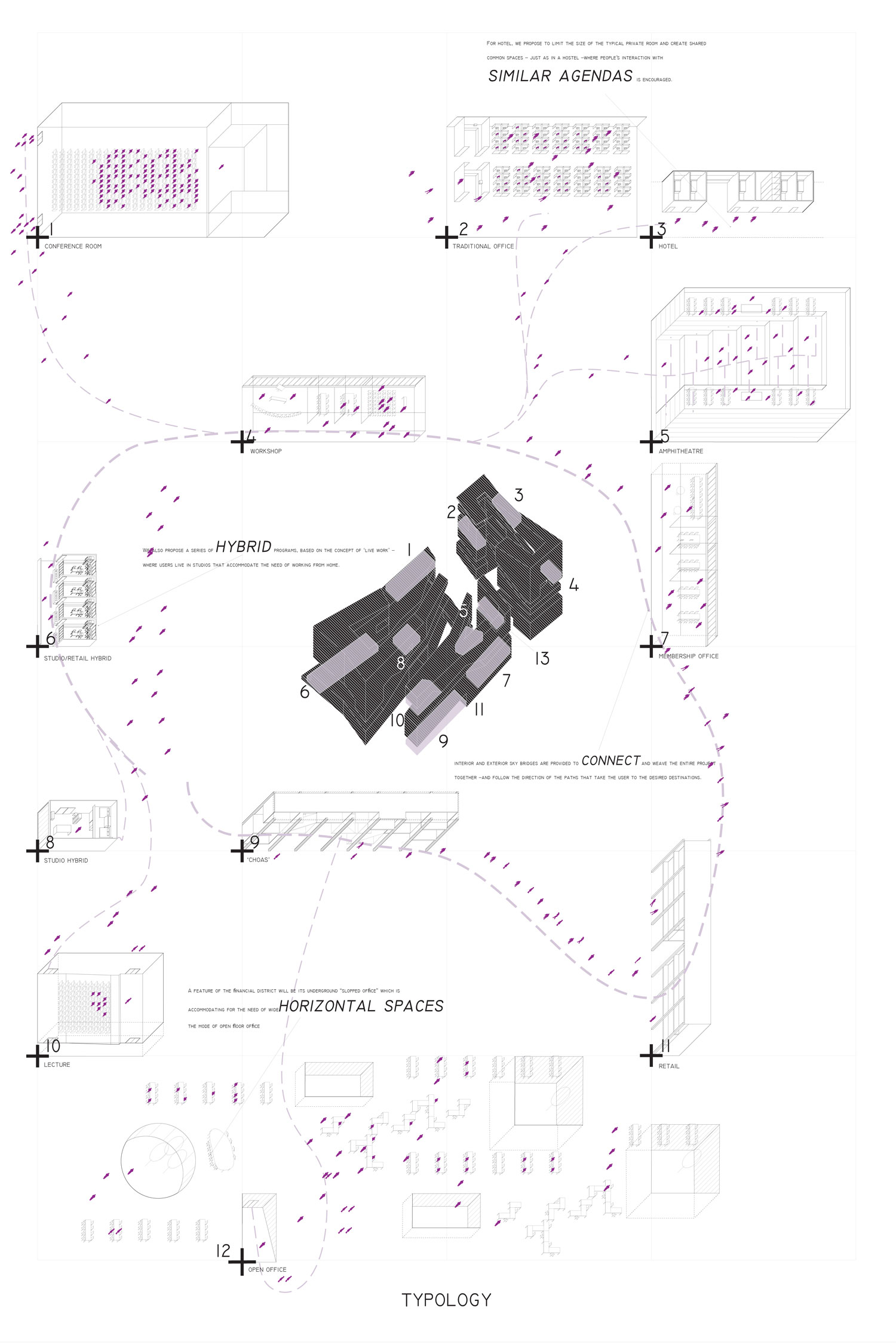

The Bhartiya city financial district serves as a model that provides a series of programmatic prototypes. These prototypes are intended to foster a culture of entrepreneurship through the promotion of interaction between businesses that are in wide range of establishment. From the level of a larger established company to the start-up level –by introducing more social condensers than the typical office building, the goal of exposing local Indian brands to an international audience is achieved. The financial district will promote the “blurring” of programmatic elements to encourage the interaction and contribution of users with similar agendas. This blurring happens through the hybridization of elements in to new programmatic prototypes and by juxtaposing work related and highly social spaces.

Revisting Lasnamae:

a 21st Century Response to the Soviet Master Plan

Team Members: Takafumi Inoue and Sabrina Ramirez-Diaz

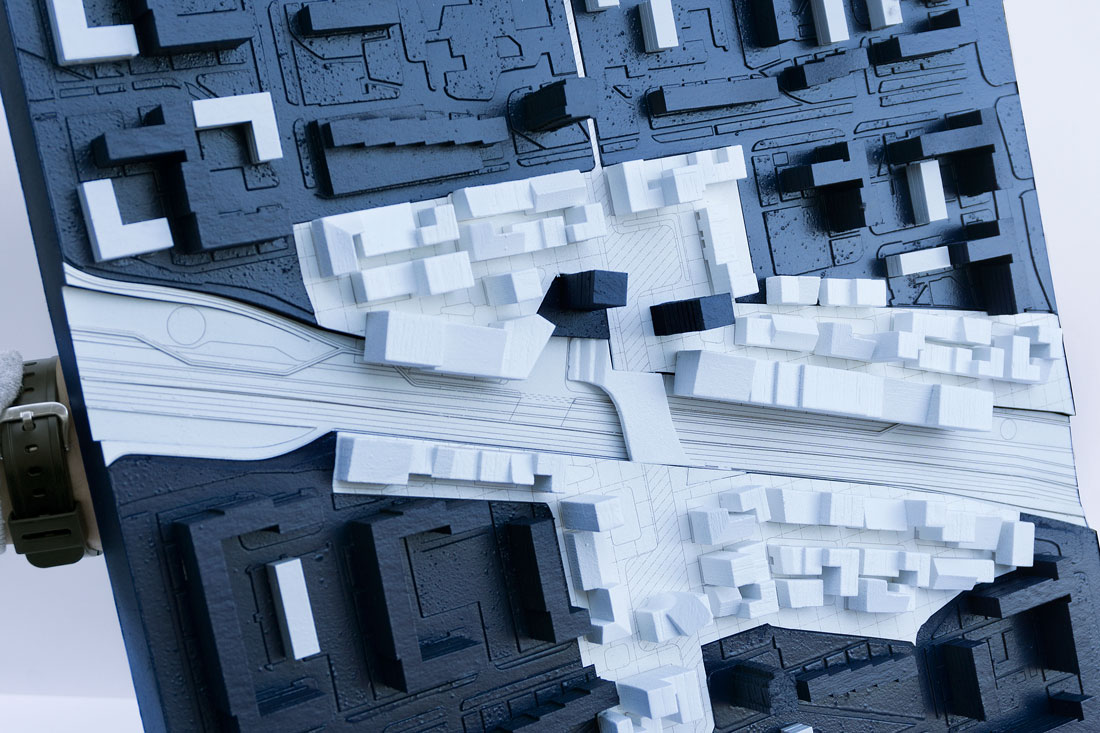

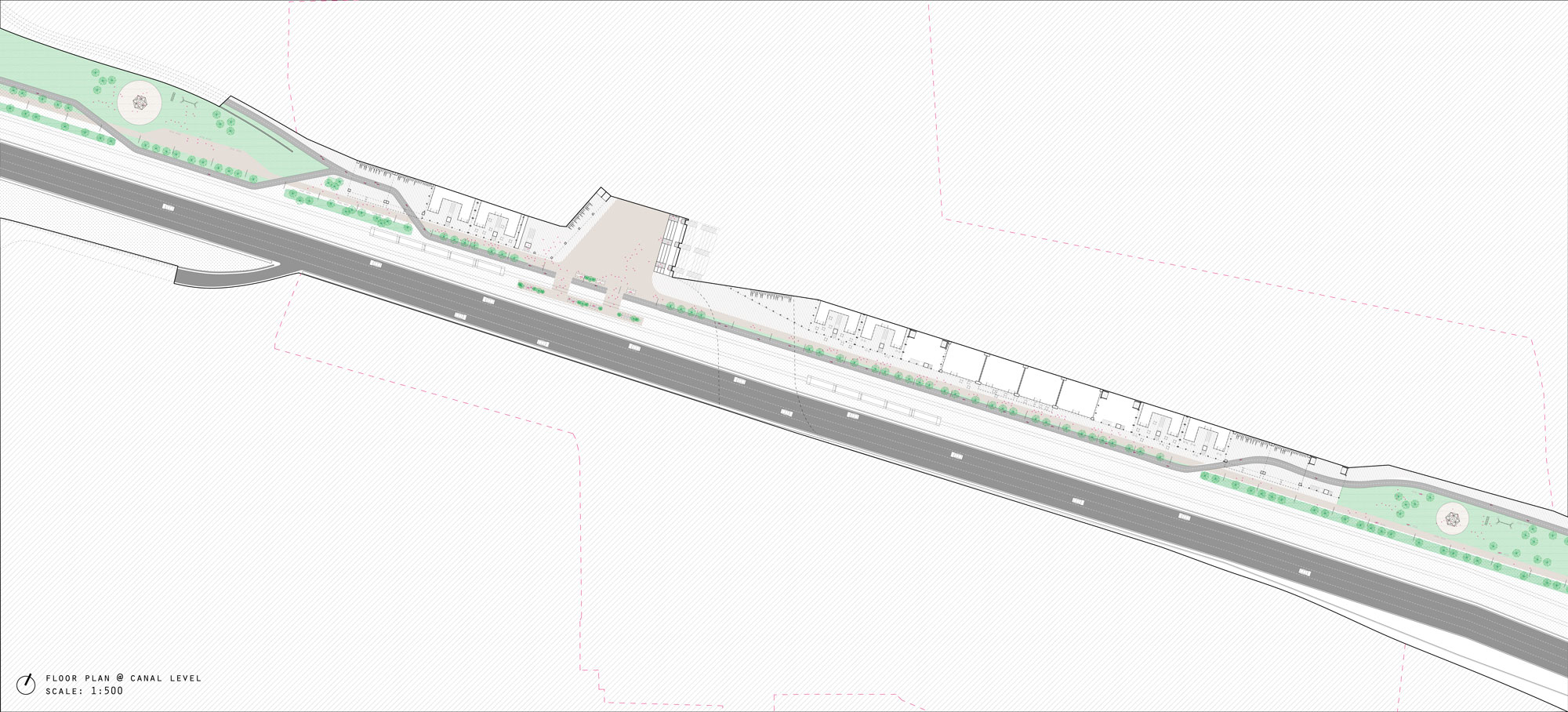

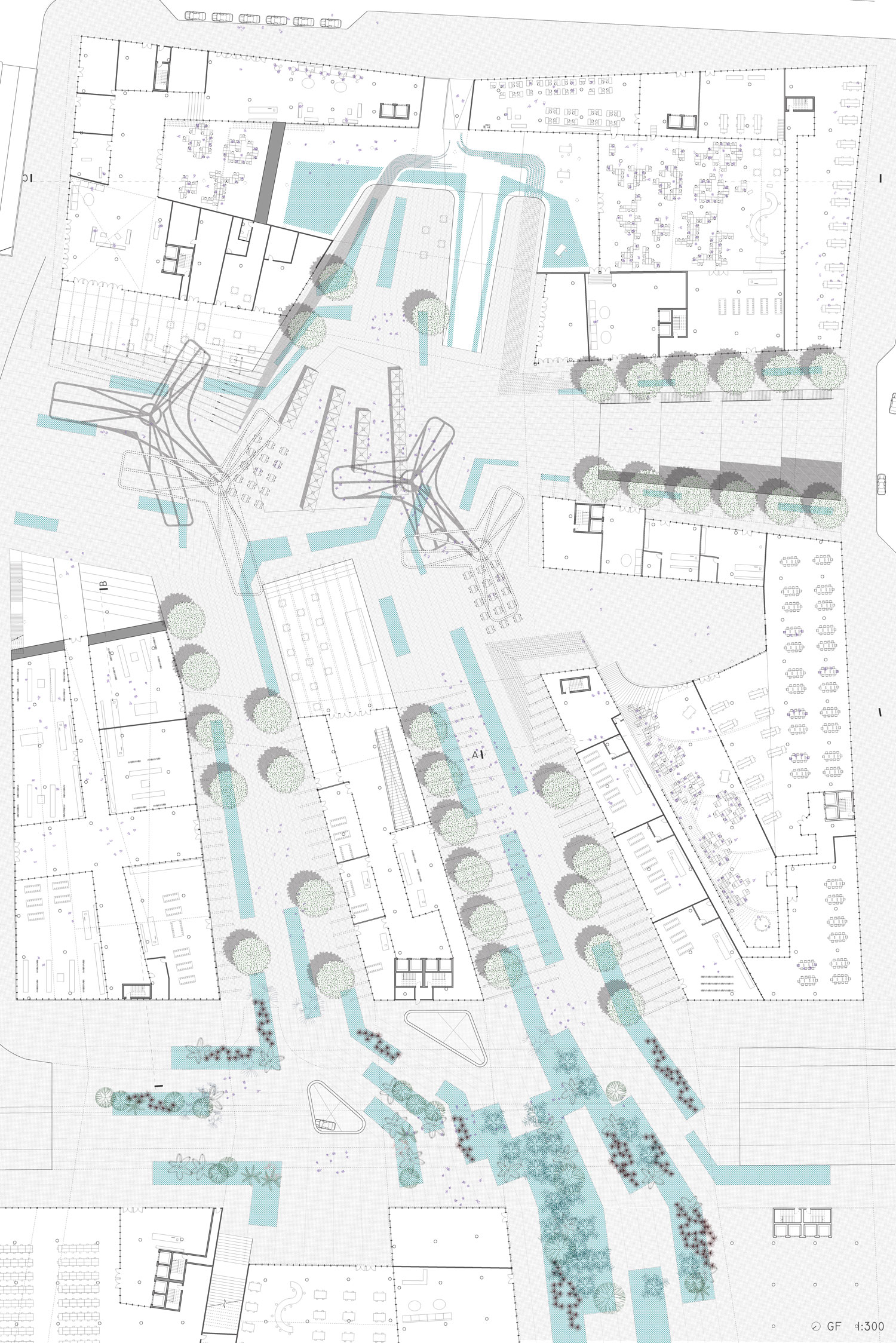

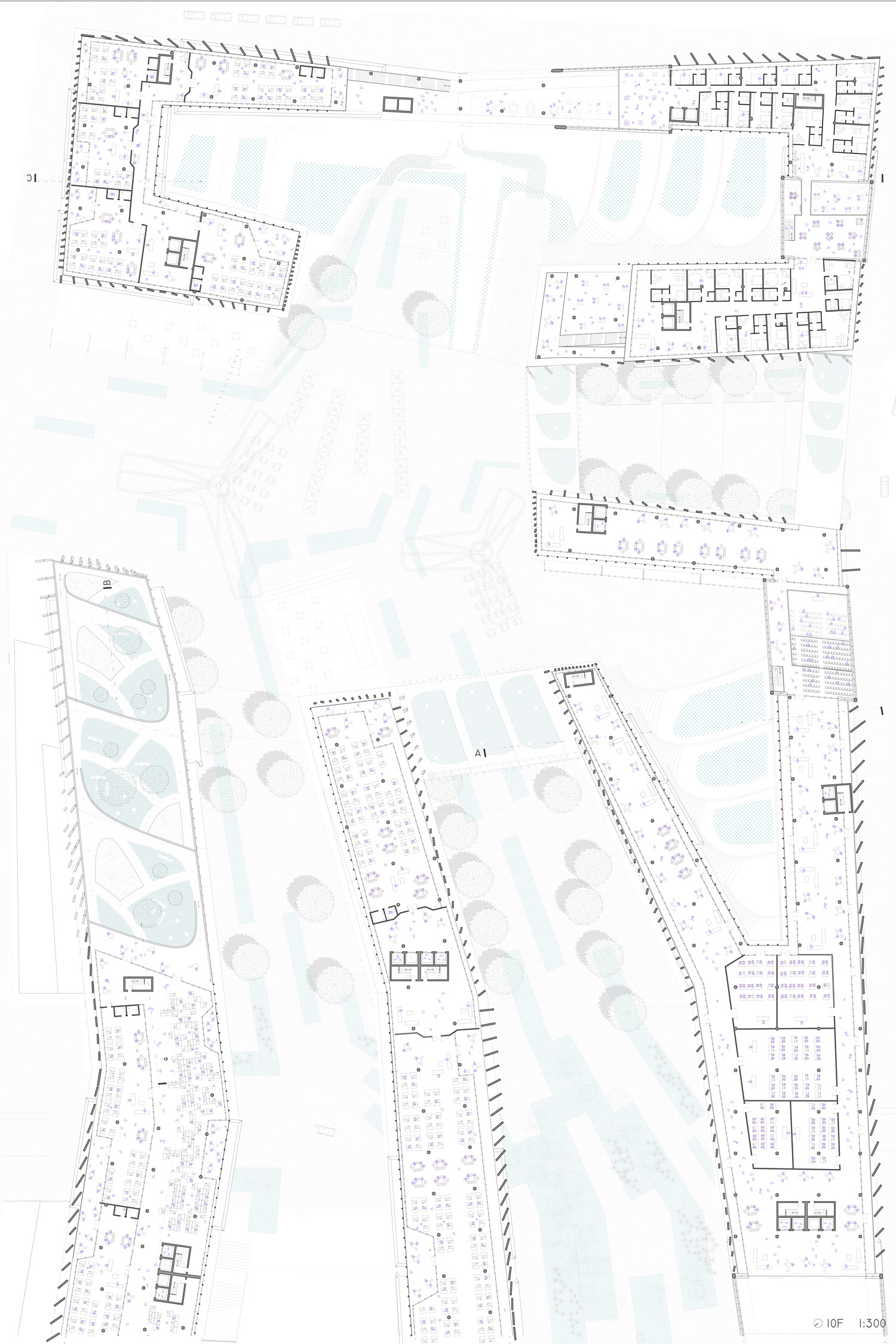

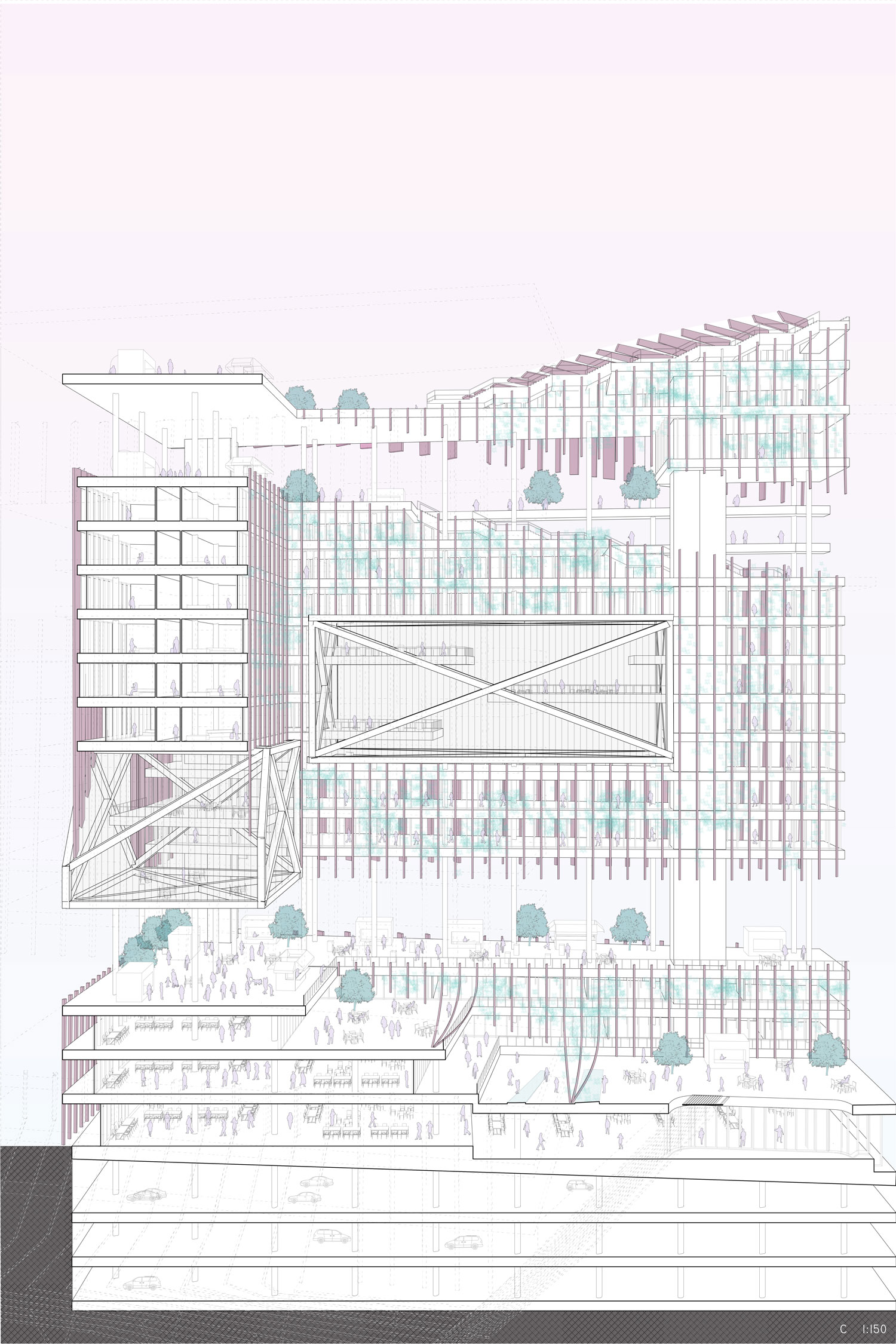

This project draws

from two earlier Master Plans for the city of Tallinn. Firstly, from Eliel

Saarinen’s 1913 Grand Master Plan for the City of Tallinn, Estonia: from its

proposed 4 mile long sunken channel, its mass transit system and its civic

squares. And secondly, from the 1970’s Soviet Master Plan’s grand urban ambitions.

Two seminal influences in the shaping of the city, but in turn, re-imagining

them for Lasnamäe’s and Tallinn’s contemporary context and needs. Despite all the great

intentions, when the Soviet Union fell, and Estonia regained its independence

the district of Lasnamäe was left unfinished. Today, Lasnamäe is considered a

dormitory district, as only residential buildings were built –and its

sub-centers remain disconnected by the very thing that was intending to connect

them.

The goals that this project took on were:

1. Continue the Soviet Plan with an agenda that served Lasnamäe’s contemporary context

2. Provide the financial mechanism necessary to allow for a revitalization of the district in a way that is feasible and sustainable

3. Stimulate a community oriented urban environment

The goals that this project took on were:

1. Continue the Soviet Plan with an agenda that served Lasnamäe’s contemporary context

2. Provide the financial mechanism necessary to allow for a revitalization of the district in a way that is feasible and sustainable

3. Stimulate a community oriented urban environment